Acoustic Mobility Device

with Carmen Papalia

September 2015–ongoing

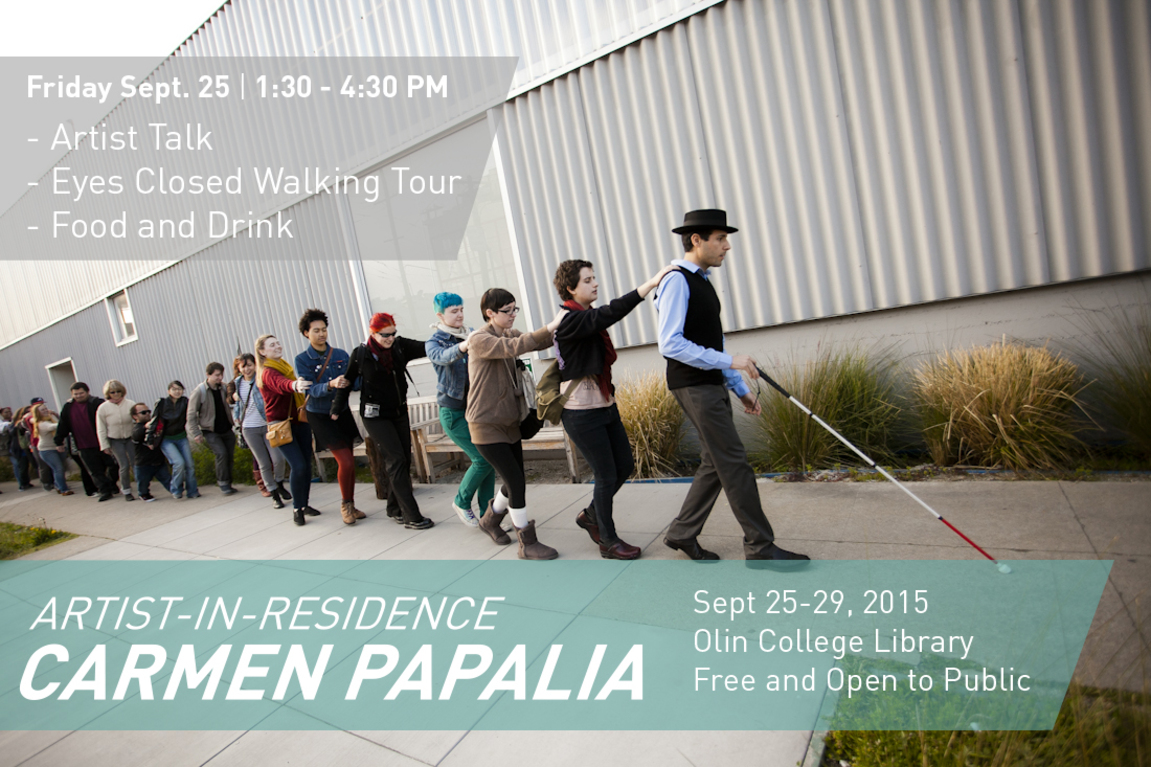

In fall 2015, artist Carmen Papalia came for what’s known at Olin as a “micro-residency”—a visit of several days that included an artist’s talk, meetings with students, class visits, and more.

Our library co-hosts guest speaker events and micro-residencies—engagements with visitors at our tiny scale.

Carmen says he’s a non-visual learner; he uses a cane and smart phone to navigate the built environment. His work has included lots of performance projects that utterly subvert the normative cultural expectations for an assistive cane. Like working with a marching band to perform instructions for a convivial audio form of navigation.

Carmen worked with a marching band to cue his navigation on a street in Berkeley, California. The band created musical directions to steer his steps.

Carmen told us about these precedent works and the context of his practice in general, which is social, durational, and theatrical. His work engages alternate sensory worlds and modes of access, broadly conceived. And he does it with such humor and irreverence.

Carmen gives an artist’s talk for students in the Olin library.

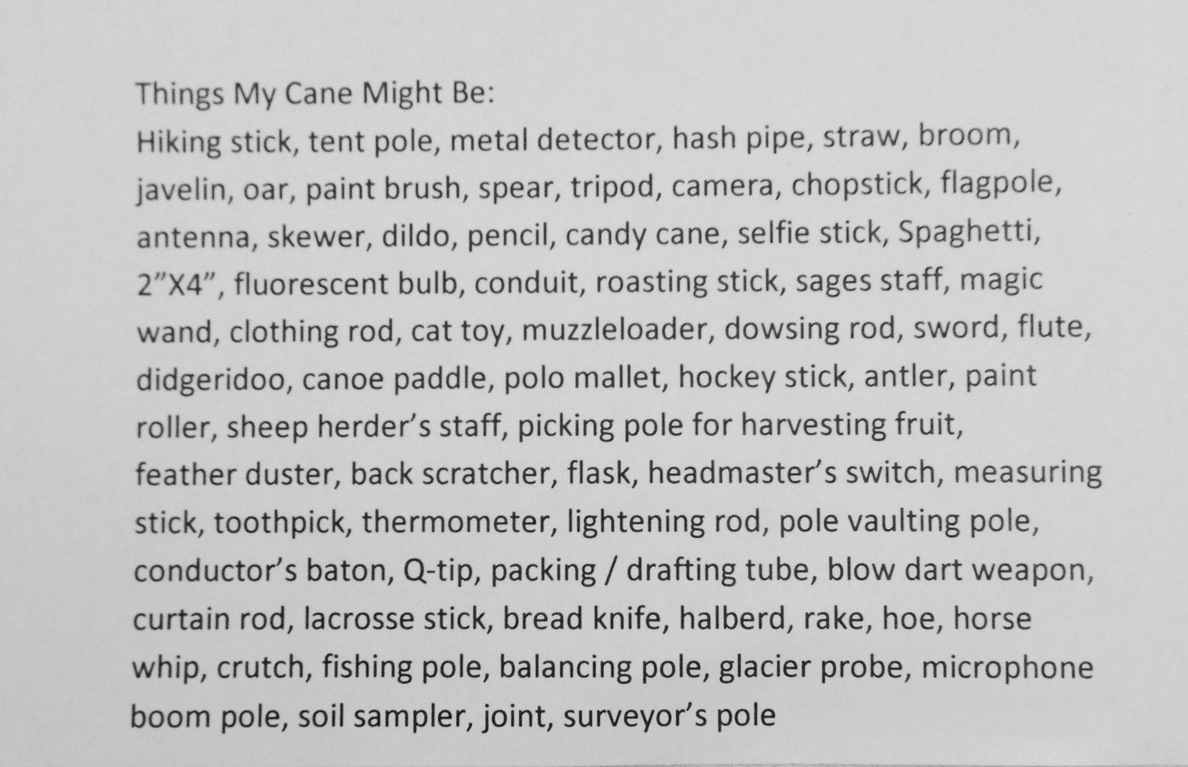

He also brought this list of things his cane might be: a provocation for rethinking expectations for technologies and tools.

Things My Cane Might Be: a list including a hiking stick, a tent pole, a metal detector or hash pipe, and a hundred other possibilities.

After his talk, Carmen led us on a “blind field shuttle”—a collaborative work he’s performed before. It’s not a simulation of blindness, and certainly not an “empathy exercise.”** It’s something else entirely: an hour walking, eyes closed, and interdependent on the person in front of you and the person behind you. We walked with one hand on the shoulder of the next person in line, and we provided a shoulder for the one after. Once you settle into the feeling, it’s blissful: an invitation to feel the sun on your face, to attend to the sounds and somatic changes of the environment. It’s an alternate form of experience.

Carmen leads a :blind field shuttle—an invitation to a long walk without using vision.

He also invited students to perform a solo walk, unsighted. Now we weren’t connected to anyone else, and we confronted our relative willingness to explore. Again, not to “experience blindness”—not at all—but to engage in an alternate sensory world.

Carmen leading a solo walk exercise, another experience of the built environment without visual cues for navigation.

Carmen came to us wanting a cane that would further this inversion of its normal functioning, and he wanted the register of technology and engineering to be foregrounded this time. He challenged us to think about a “reverse” cane—one that would actually perform loud, even aggressive sounds, like an instrument.

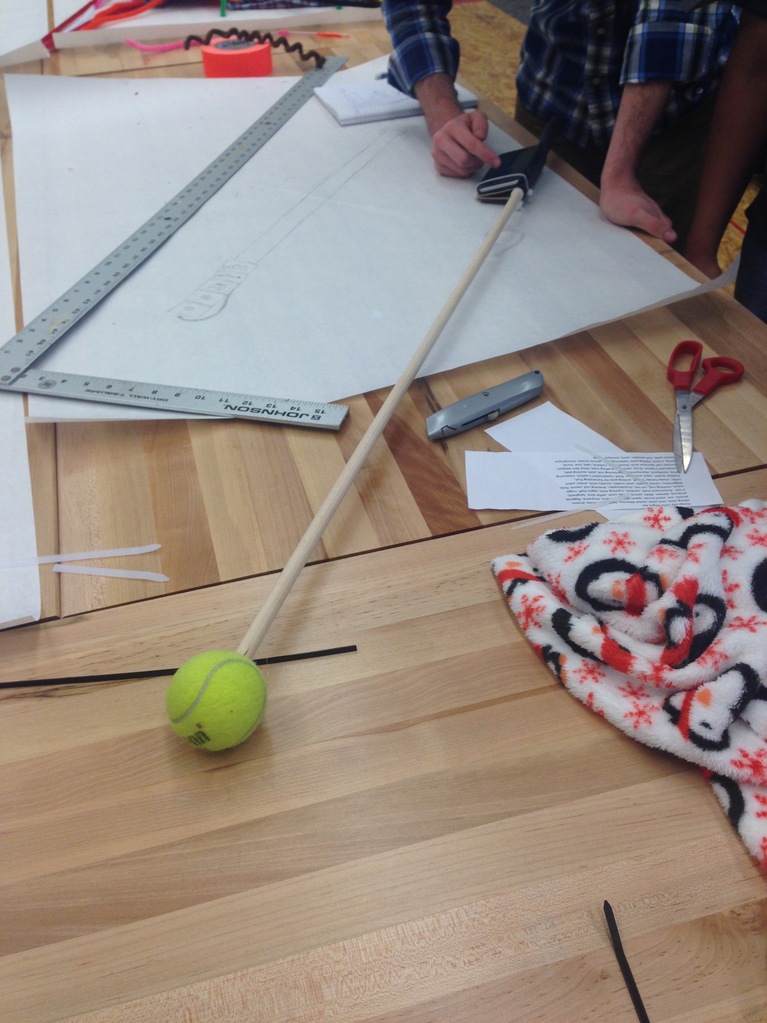

During his visit to Investigating Normal, the whole class rapidly sketch modeled some possible ways to think about a performative cane: wearables and wiring and amplification of various kinds.

Carmen wears a sketch model of sensing “whiskers” that would cue the cane to make sounds as Carmen gets nearer or further from an audience on the street.

A smart phone set of musical tracks and sounds was mocked up with a tennis ball for playing.

A close up of the smart phone/tennis ball model.

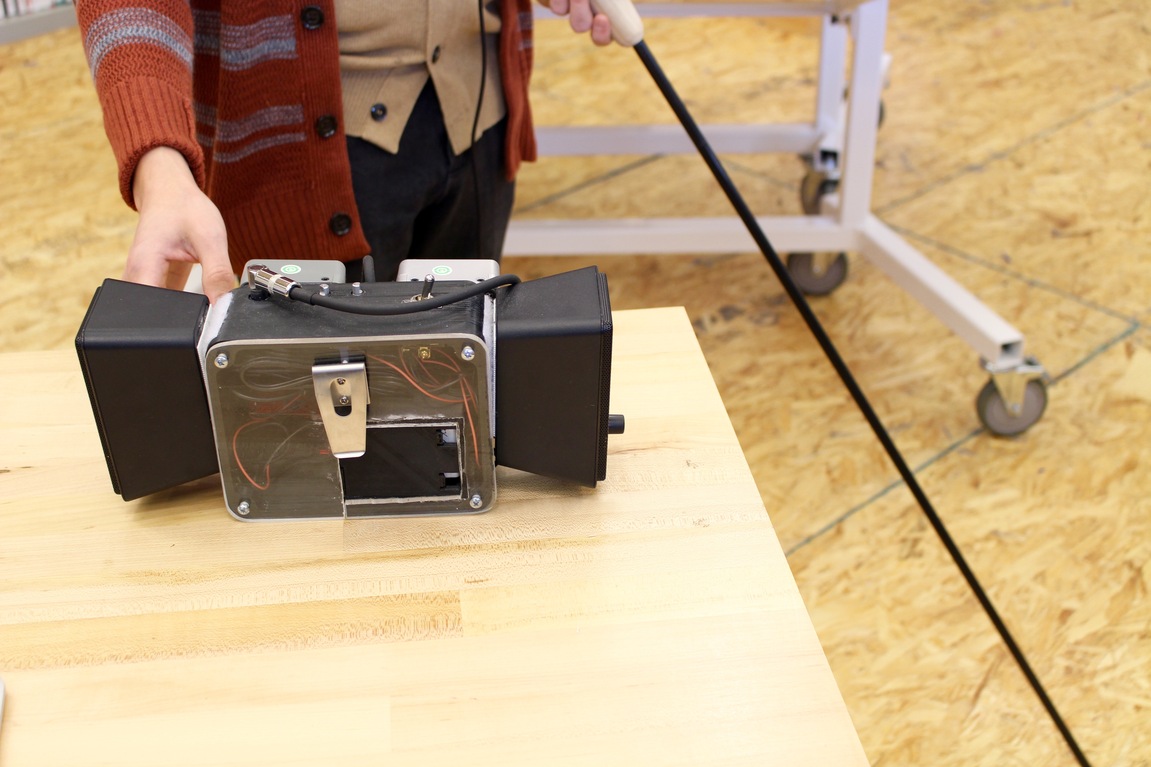

Most promising was patching together a microphone and an amp, for “playing” the cane across carpet, wood, textured surfaces.

Students wire together the amped cane sketch model.

Carmen tests out the amped cane with students looking on.

The team pursued this last idea over the following months: a cane outfitted with a microphone and connected to a battery-powered amp that could be worn on the body, like an old school jam box and prosthetic instrument, all at once.

Carmen tests out the 1.0 prototype, with a clear back of plexi over its power source.

We’ll update here with formal photos from a performance. We’re still getting the final prototype done in the lab. More to come!

One of the beautiful things about this kind of design work is in the ancillary products and processes that result. Student Daniel Leong documented the process by which he planned an interrupted 3D print for the end of the cane that would house the contact mic.

**See this post for a discussion of the manifold problems with the disability simulation exercise. There are alternatives to this well-meaning but fraught practice.