Alterpodium

with Amanda Cachia

March 2014–ongoing

Amanda’s collapsible, lightweight carbon fiber podium: provisional interior architecture for short stature.

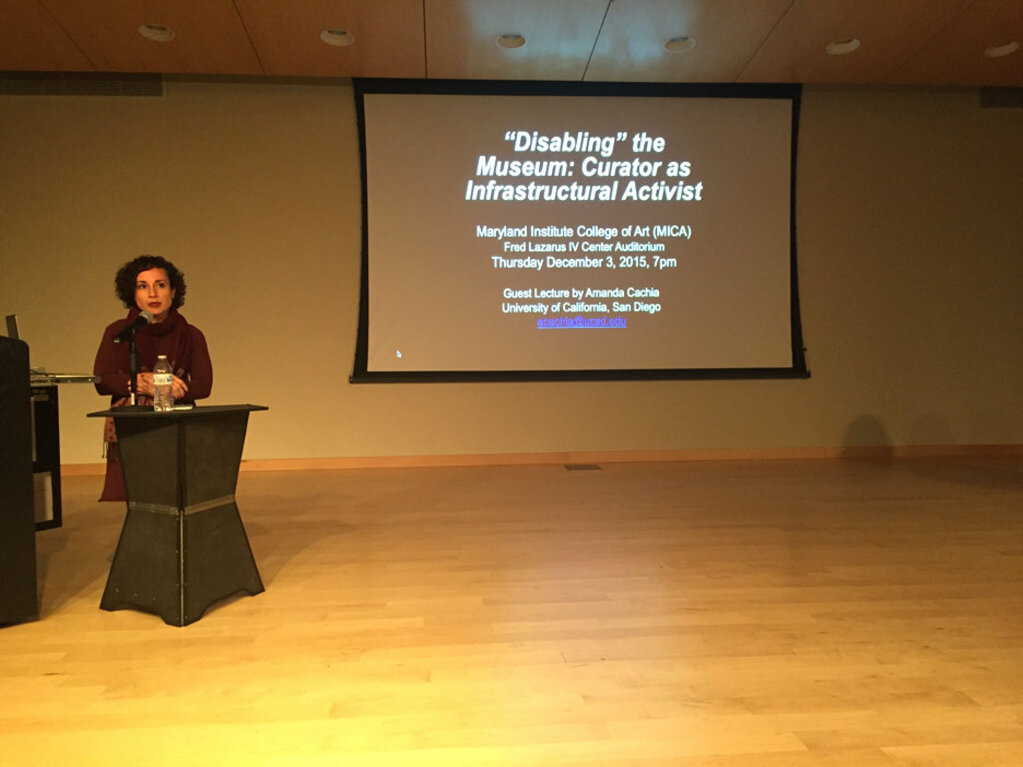

Amanda Cachia is a curator, an active scholar, and an art historian-in-training at the University of California, San Diego. She travels constantly for lectures and gallery talks, so she’s in front of people in rooms a lot. That’s her on the left, below.

Amanda speaking at a conference, standing at a typical podium with steps or other supports to reach its height.

But the architecture of lecture halls, stages, and furniture is scaled to humans generally well over five feet tall. And Amanda is considerably shorter: she’s 4’3″. In the photo above, she’s standing on steps so she can reach the height of the lectern.

Amanda’s curatorial work sometimes addresses this very discrepancy: how atypical bodies pose questions about standardized notions of “fit” for built structures. So, in a lecture she gave in 2012 during a California College of the Arts symposium, she wanted not only to rhetorically discuss this discrepancy, but to perform it. She had a podium built precisely for her stature, designed by Shawn Hibmacronan and built by Adrien Segal. This wooden one, below:

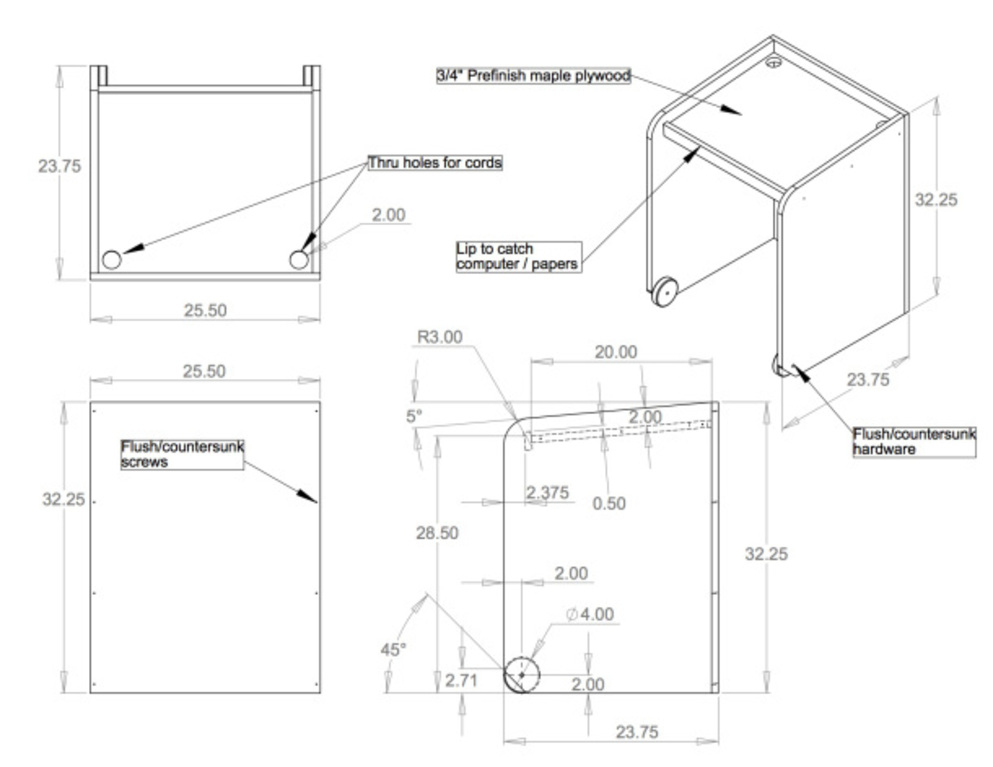

A wooden podium, designed like a typical lectern, but at smaller scale.

Drawings with dimensions for Hibmacronan’s original design.

Using a smaller-scale lectern was so effective—as an idea, and as a design—that Amanda decided she wanted one that was portable, to take with her to every lecture event or gallery talk she gives.

In 2014, she went to Sara with a challenging but irresistible design brief: to create a collapsible, lightweight, sturdy podium that could go with her anywhere, in her suitcase.

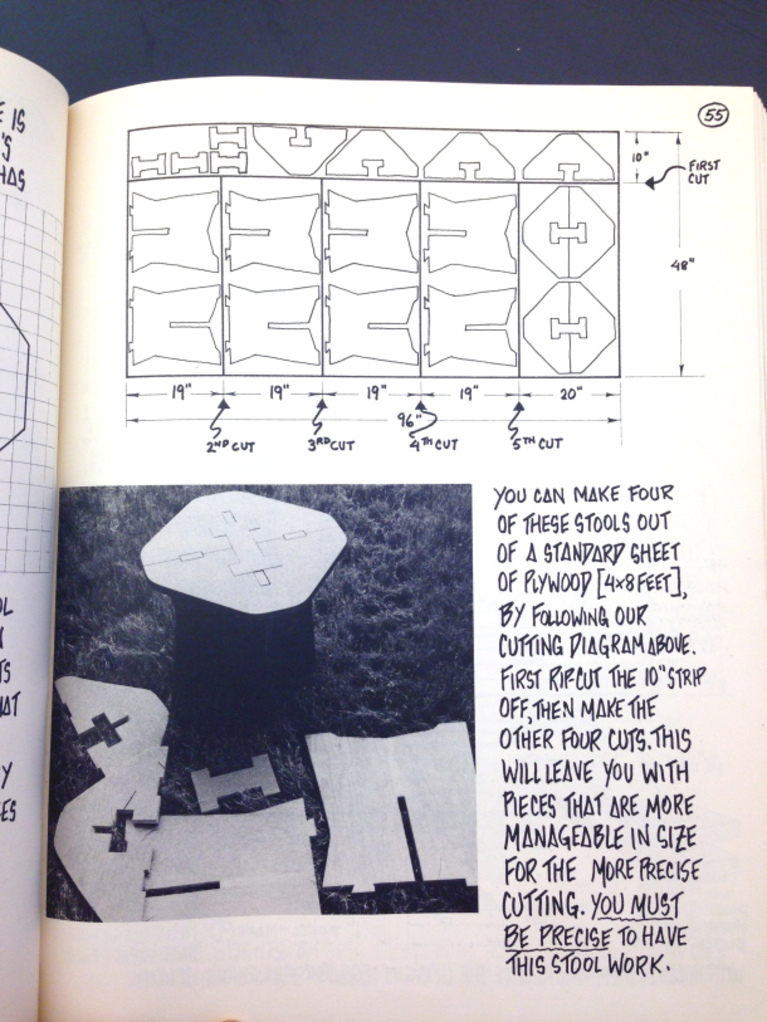

Sara started thinking immediately about Victor Papanek’s “nomadic furniture,” like this set of stools that can be assembled from a single piece of standard plywood and disassembled quickly.

An image from Papanek’s Nomadic Furniture book shows how to get four stools cut from a single piece of plywood.

The Cambridge design-and-fabrication storefront, Danger!Awesome, helped Sara think through this early model with architectural designer Michael Velentzas assisting on a no-hardware prototype that would pack lightly, cleanly, and be structurally stable.

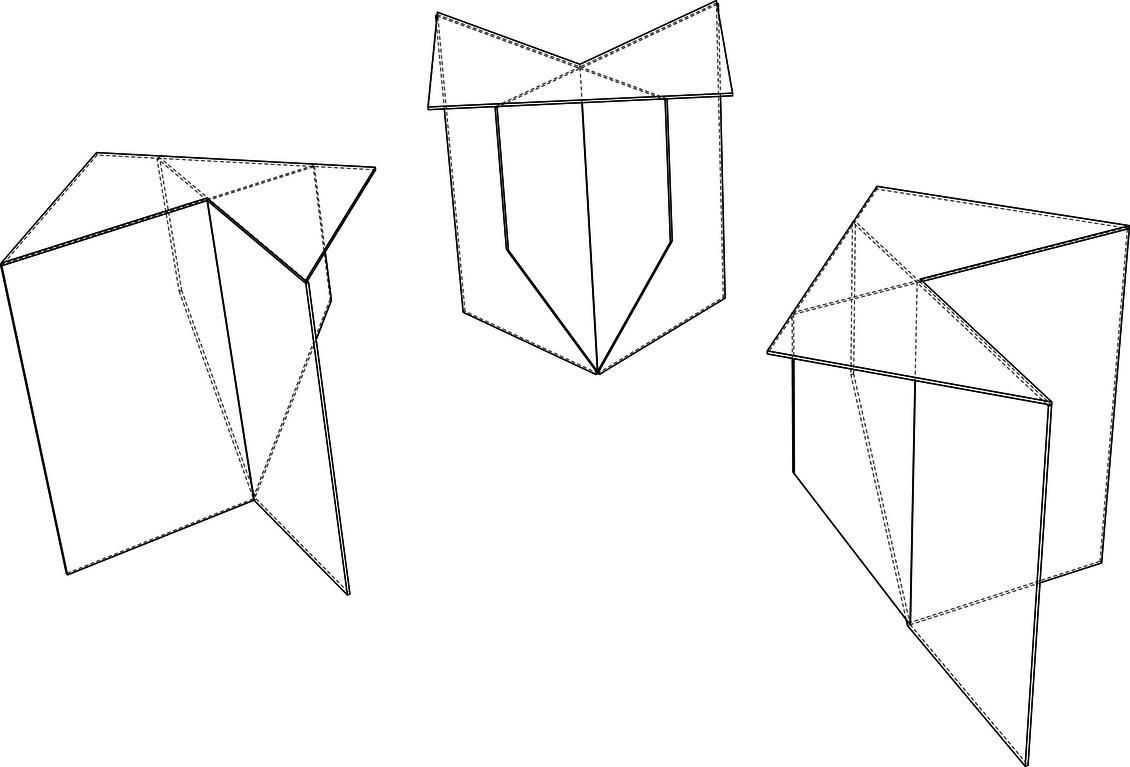

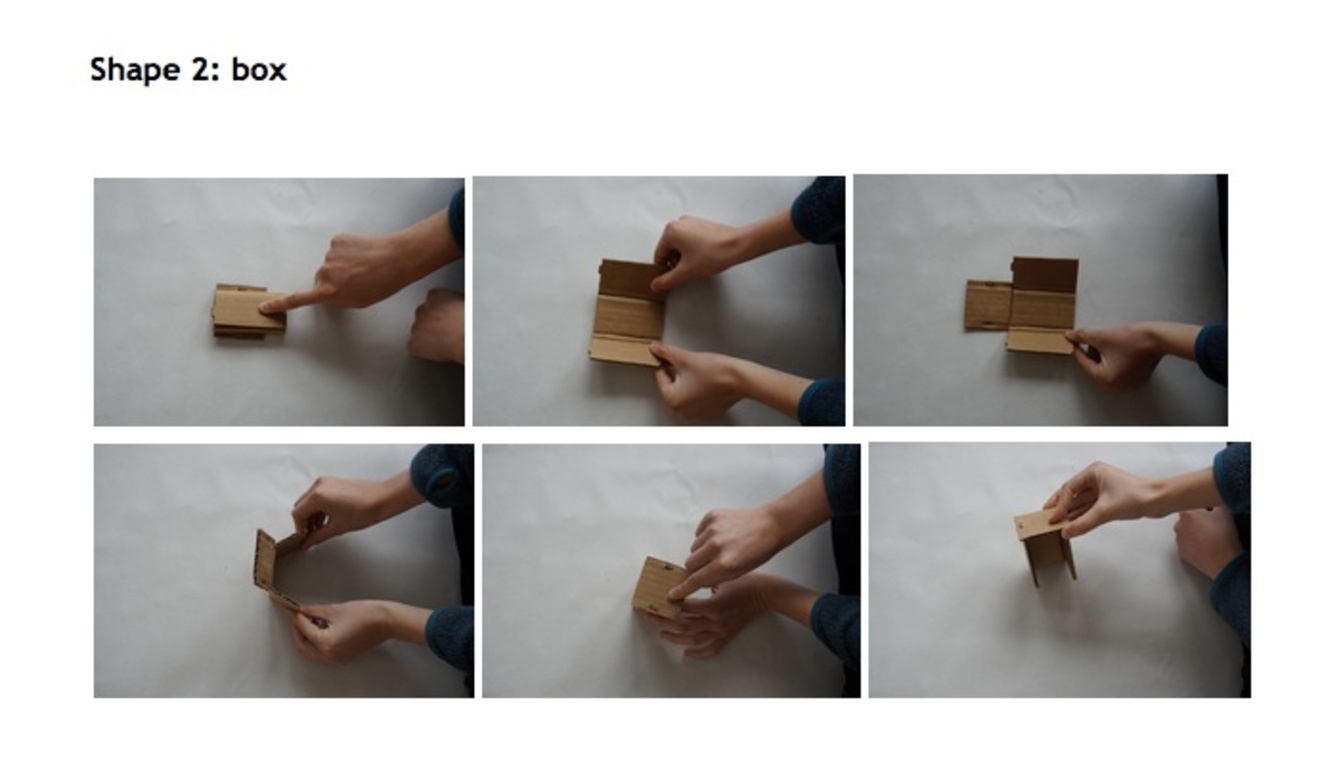

We messed around with paper models and arrived at this strong triple-wall cardboard model:

A CAD rendering of the foldable cardboard model

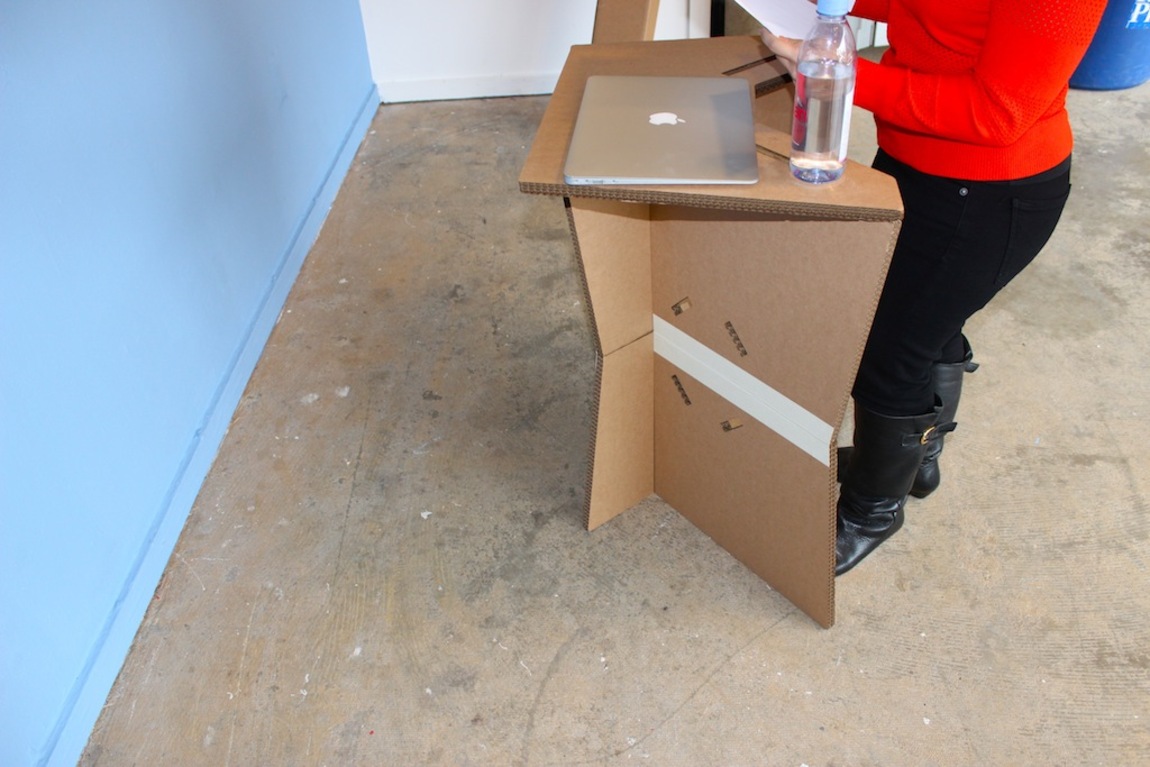

And in March, they met at a conference in New York, where Sara delivered her the cardboard prototype: Just three pieces, barely hinged together with tape, and with enough material friction to make it hardware-free, lightweight, but strong.

Amanda stands at the cardboard podium, testing its dimensions for her height and surface area needs.

Amanda found this basic model to be a good working prototype.

From the beginning, this model was meant to be partly prototype, partly performance. So Amanda and Sara took the opportunity of the conference to try out its registers in time and space, as more than just a product. They arranged it so that when Amanda was introduced as part of her panel, Sara would silently go to the front of the room, and there assemble the podium, in real time.

Sara building the podium, attaching the pieces of cardboard together.

They did this without commentary, and Amanda gave her talk—also without commentary. And then they spoke with the audience about it afterward.

There was something so magic about seeing this quick reversal of scale. Usually Amanda’s embodiment comes to the architecture of the room. She adjusts to it. But here, the architecture suddenly came to her—at least provisionally. It was like the scale of the built environment shifted in real time. It was her idea to call it an “alterpodium,” following theorist Nicolas Bourriaud’s coinage of the “altermodern”—a way for cultural producers to critically engage with the facts of globalization and standardization without merely nostalgia for locality or craft.

But Amanda needed a permanent solution, and for that she came to Olin in spring 2015.

Amanda visits the class, cardboard model in hand.

A team of four engineers then worked to come up with a design and material that would fold flat, stand up to frequent travel, be strong and lightweight. They tested a bunch of geometries in paper:

Two hands hold a paper sketch model for a lectern, testing its geometry and folding logic.

A set of image showing hands walking through the fold possibilities for one sketch model.

Eventually, the team decided on carbon fiber for their final version. We all loved the high tech associations of carbon fiber, in addition to its functional properties. A material mostly used for aerospace and automotive applications, brought to another life in a bit of interior architecture for short stature. The best kind of juxtaposition.

Engineers at work on a carbon fiber layup—curing it for a strong seal.

A close up of the carbon fiber layup.

Amanda has lectured with the Alterpodium at a number of events over the last year. We may need to do a 2.0 version for more robust life. More to come. Look for Amanda’s essay on the project in an upcoming issue of Design and Culture.

Amanda performs her podium at a speaking event, with her model next to to the typical scale design.

Amanda performs her podium at a gallery opening.

The finished(?) project again, in one, two, three steps.